NOTHING BUT ARCHITECTURE

Stan Allen

“Nothing but architecture." To begin in this way would appear to be deliberately disingenuous. John Hejduk, after all, has been recognized for his unique ability to colonize architecture's sometimes remote margins. If the designation "nothing but architecture" is self-evident and adequate as a beginning, it is just as self-evident and inadequate as a conclusion. I have borrowed his formulation from Jean-Luc Godard. Writing about American filmmaker Nicholas Ray, Godard observes : "If the cinema no longer existed, Nicholas Ray alone gives the impression of being capable of reinventing it, and what is more, of wanting to." Only in Nicholas Ray, Godard believes, is the vocation for cinema so deeply felt : "Were the cinema suddenly to cease to exist, most directors would be in no way at a loss; Nicholas Ray would." The paradox, in the case of Hejduk, as with Godard, is that the passion for a vocation has provoked an uncertainty regarding the very limits of that vocation. Godard anticipates Hejduk's doubt : "The whole cinema and nothing but the cinema, I was saying of Nicholas Ray. This eulogy entails a reservation. Nothing but cinema may not be the whole cinema."1

"Nothing but architecture" and "the whole of architecture" : two intersecting, non-identical sets. "Nothing but architecture" functions reductively, beginning with the known and working always back toward the known. "The whole of architecture" is a shifting, provisional fiction. Like Godard, Hejduk operates in the uncertain territory where these two sets intersect. Hejduk is an essentialist, a conservative for whom "nothing but architecture" is already given. Everything else — poetry, books, music, teaching, theater — is the mark of Hejduk's doubt : could "nothing but architecture" ever constitute the "whole of architecture" ?

Theory I : "Modern Masters, Late Modernists"2

-

Procedures are not merely the objects of theory. They organize the very construction of theory itself. Far from being external to theory, or from staying on its doorstep, [these] procedures provide a field of operations within which theory is itself produced.3

The conventional assessment of Hejduk's accomplishment is that it moves architecture away from practice, and in the direction of theory.4 For example, "Outside Practice," the title of a 1992 Chicago exhibition of Hejduk's work, suggests that Hejduk's contribution is located outside the realm of conventional practice, and by implication, saturated by practice's opposite, the theoretical. Others have suggested that the drawings, models, narratives, and constructions emerge from a primary reflection on architecture itself, which has necessitated a withdrawal from the contingencies of practice. Hejduk, this argument goes, wins for himself an unprecedented freedom of inquiry on the condition that he not intervene in the world at large. This reading would locate Hejduk's work in the overarching and persistent territory of linguistic structures rather than in the individual utterance. This results in part from a simple confusion of the realm of the project — the speculative, the hypothetical — with the realm of the theoretical. Just where is theory in Hejduk's work, and how is it possible to disentangle it from the specific instance, the particular case ?

A close examination of the work, I propose, would suggest just the opposite : that in this work, nothing of theory Cas conventionally understood) remains. In proposing this, I want to move beyond the obvious fact that Hejduk never presents an abstract thought about drawing, language, narration, or building; rather he presents drawings, language, narration, and buildings themselves. Hejduk resists the theoretical not out of anti-intellectualism or antipathy to thought in architecture, but in recognition of theory's tendency toward reduction, regulation, and repetition. Rather than submitting each example to the rule of theory, Hejduk elevates the individual utterance to the status of the general. Hejduk's "field of operations" in turn produces something like theory, but more fluid : a systematic thought capable of accommodating architecture's status as a non-circumscribed discipline.

The invention of theory and the codification of architecture as a discipline went hand in hand. For Renaissance theorist Leon Battista Alberti, the production of theory had a concrete political end: to incorporate architecture into the circumscribed body of the liberal arts. This could be accomplished only by differentiating architecture from journeyman craft, extending the privilege of the "royal sciences" to architecture.5 For this codification to be effective, it was necessary to institute an opposition between the "speculative" and "practical" aspects of the arts. As Michel de Certeau writes, "Art is thus a kind of knowledge that operates outside the enlightened discourse which it lacks."6 The space of theory must be delimited in order to reflect at a distance on the "nature" of the discipline, while the possibility of cumulative or incremental change from within the discipline must be held in check. Theory and practice are, under this formulation, equally rule-bound : theory is devoted to the production of rules, while practice is relegated to the habitual implementation of those same rules. The "royal sciences" provide the arts with constructed, regulated, and thus "writable" systems : organized from without on the basis of that which they themselves lack.

The Modern Movement inherited this theoretical apparatus in a nearly exhausted form. The classical codes of mimesis, canonical proportions, and the orders were patently inadequate to confront new aesthetic and functional demands. New technologies, and new building typologies, provoked a rethinking of the conventionally defined relation of theory and practice. Moreover, the tendency of academic theory to resist practice-driven change rendered it suspect for the architects of early modernism. As Walter Benjamin points out, innovation in the nineteenth century occured outside of academically sanctioned practice. But far from denying the efficacy of the theoretical per se, the modernists revised its terms and redeployed its strategies with a high degree of operational effectiveness — they colonized its margins. "New forms in art are created by the canonization of peripheral forms" writes Viktor Shklovsky.7 The production of manifestos, didactic exhibitions, and pedagogical programs had the effect of capitalizing theory's margins. Rather than challenge the role of theory, the paradigm shifts of early modernism demonstrated precisely the ideological power of the theoretical idea. In order to achieve operational effectiveness, the essential separateness of theory and practice was upheld. The result was to maintain and promulgate the classical notion of theory as writable codes: hierarchical and disengaged; systematic and prescriptive.

Only in the postwar period, when the theoretical precepts of early modernism became ossified into a set of unarticulated professional codes, did the urgency of the theory / practice question emerge as a problem. The ideological impulse of the prewar avant-garde had, by its very success, been institutionalized as a series of strategies for the implementation of a program of universal modernism. In the postwar period, the modernist impulse proceeds not from the margins (the avant-garde practice of negation) but from above (the programs of multinational corporate capitalism). The late modernist is presented with mutually exclusive and equally unacceptable alternatives: either to adhere to the rigid but unwritten dictates of professional practice, which incorporate, in degraded fashion, the theoretical positions of early modernism; or to attempt a "utopian" recovery of the space of the avant-garde, now operating as neo-avant-garde to rewrite (in highly self-conscious terms), the pretexts of early modernism. In the United States, which was never entirely sympathetic with the ideological agendas of modernism, this split was especially pronounced. As Colin Rowe has put it, in America after the war, a commitment to the modern entailed a decision : should the architect adhere to the physique-flesh or to the morale-word8 of modern architecture ? Mainstream practice chooses the physique-flesh; the neo-avant-garde signaled its distance by foregrounding theory.

Hejduk inherits this late modern distrust of the "morale-word," yet he finds it unsatisfactory as the basis for sustained work. This is the double bind of the late modernist : to be at the same time "modern" (i.e., committed to progress and continual innovation) and a latecomer — heir not only to an established formal canon, but to its exhausted ideological apparatus as well. Hejduk's lateness consists in recognizing the impossibility of the panoramic view and the foreclosure of certain options.

-

-

Wall : Do you feel that Frank Lloyd Wright completed his work ? Hejduk : Yes. Wall : And Corbusier also ? Hejduk : Yes, all those architects really completed their work. Wall : But you mentioned that Corbusier should have done a Diamond House. Hejduk : Yes, but they completed their work in a panoramic view. That's what made them masters. I am like a fly that comes in and says "OK, here is one aspect that has been left out, yet which has great potentiality, it should be wrapped up."9

The late modernist inhabits a field marked by the immense theoretical effort necessary for modernism to invent itself. However, the panoramic "space apart" — the realm of theoretical reflection — is denied to him. He is aware that his options have been limited. His only choice, then, is to begin to articulate theory concretely through the space of its procedures. Hejduk restrategizes the conventional use of theory understood as legitimation from outside (an appeal to that which art lacks) by systematizing practice from within. He enacts systematic thought not only within the institution — according to an already given set of rules — but as the production of new rules (or new institutions) according to the logic of his own practice, which provokes and exceeds theoretical description. From this belated position, he recognizes that architecture is already exhaustively theorized; there exists no space outside from which one would think architecture without being implicated in practice.

Hejduk's belatedness and his antipathy to theory are therefore bound up with one another. The late modernist must simultaneously negotiate both his or her own "lateness" and the recent death of the modernist theoretical project. Hejduk seeks to recover something of the urgency of the Modern Movement's original refusal — an oppositional stake in the morale-word — but with the knowledge that the stakes have changed. Now they can only be internal and individual. His desire for the panoptic spaces of modernism is at odds with his knowledge that these spaces have been lost. As a result, Hejduk is committed to the modern as practice, not as project.

Hejduk's refusal of theory is a refusal of theory understood outside of, or apart from, the operational space of its procedures. Practice can never simply be the object of theory. Moreover, theory and practice cannot even be defined apart from a series of systematic exclusions. Like Josef Beuys "explaining pictures to a dead hare," Hejduk's practice of theory gives up totalixing explanations as absurdities. It can only explain itself to itself The speculative and the practical, held apart in both the modernist and the classical, are productively collapsed in Hejduk's work.

Theory II : “A Minor Practice" ?

In attempting to name and describe the practice that results, I would be skeptical of the temptation to designate Hejduk's a "minor" practice in the sense proposed by Gilles Deleuxe and Félix Guattari in their study of Franz Kafka.10 George Steiner has written that "Kafka was inside the German language as is a traveler in a hotel... the house of words was not truly his own."11 A minor practice constructs a line of flight with the materials at hand — the impoverished elements of the dominant language. Hejduk, on the other hand, is very much at home in the (now) dominant language of modernism (which might at one point have been a minor practice within the classical). Rather than a line of flight toward exteriority and collective enunciation, his movement is inwards, incorporating, enveloping, and naturalizing that which might have been at one time "other."

A more productive literary, or rather literary critical analogy, to Hejduk's practice might be found in Harold Bloom's analysis of the complexities of poetic influence. Bloom notes that "strong poets make... history by misreading one another, so as to clear imaginative space for themselves."12 By this account, Hejduk's "severe poem" battles "unwisely" against the influence of Le Corbusier or Mies van der Rohe. This is clearly marked out as an Oedipal struggle, and as such will always risk failure : "Catastrophe," writes Bloom, "seems to me the central element in poetic incarnation."13

Confirmation of this reading can be found in an often overlooked aspect of the description of a minor practice. In Kafka : Towards a Minor Literature, Deleuze and Guattari note the importance of paying close attention to the musicality of writing and the precise tonal character of Kafka's language : "Kafka too, is a minor music, a different one, but always made up of deterritorialized sounds." A minor language, like the minor key in music, disquiets the listener : "Almost every word I write jars up against the next."14 To compare Hejduk's work to a "minor key music" is plainly counterintuitive. His formal language, his gestures, and transitions are fulsome and major-key. Discordant juxtaposition is rare. For this reader / viewer at least, Hejduk, like Richard Serra, who once announced "I don't do 'minor' sculptures," remains in both the parts and in the assembled whole, major, not minor key.15

Yet another detail affirms the distance between the practices of the writer from Prague and the architect from the Bronx : Kafka's request that upon his death his works be destroyed, thereby confirming their minority status. Hejduk, on the other hand, is an obsessive archivist who continually puts his affairs in order. His projects are drawn with a precision that might allow others to eventually realize them, anticipating a moment when, no longer at the margin, they become major. Hejduk's withdrawal then, is a paradoxical retreat quite unlike Kafka's. In this regard it is interesting to take note of a recent phenomenon that has significant implications for the question of practice. As students or other architects take it upon themselves to realize Hejduk's drawn projects, a new relation of author / architect to work emerges. This process accentuates the historically produced distance or separation of the architect from the execution of the work. The notational logic of architectural representation is, with these realizations, taken to an extreme : like a piece of music whose authenticity is guaranteed by the logic of the score, the works can exist over time, apart from the autographic contact with the author, at a distance and in multiple copies.16

This coincides with a sense that Hejduk's work was already completed a number of years ago and that the recent projects are in fact already variations and copies. In this sense, the work of the past years is a panoramic summing up, an ordering and clarification. Hejduk writes : "I guess because I am a very ordered person. I am organization prone. So if something is left out, then I feel it should be completed. If you put ten blocks down and take block number seven out, I want to put it back."17 Hejduk's oeuvre is both open and closed : closed in that it has been brought to conclusion, resolved and completed; still open in the sense that it exists as a nearly infinite catalog of possible constructions and combinations of constructions that may be realized in the future. A new sense of time pervades the work of construction which provokes yet another paradox. If Hejduk, by this redefinition of practice on his own terms disappears as authoritative individual author, he reappears as architect in the broadest, that is metaphysical and theological, sense of the term — a form-giving figure capable of structuring vast assemblages from a distance. From a position of withdrawal, Hejduk wills others to carry out his work, even if he is not present to do so.

Practice I (Section A) : 18 “An Architecture of Pessimism"

Project : Cemetery for the Ashes of Thought

-

The metaphysicians, when they make up a new language, are like knife-grinders who grind coins and medals against their stone instead of knives and scissors. They rub out the relief, the inscriptions, the portraits, and when one can no longer see on the coins Victoria, or Wilhelm, or the French republic, they explain : these coins now have nothing specifically English or German or French about them, for we have taken them out of time and space; they now are no longer worth, say, five francs, but rather have an inestimable value, and the area in which they are a medium of exchange has been infinitely extended. Anatole France

Hejduk's obsession with naming, categorizing, and control can also be understood as a way of articulating its opposite: the futility of naming, categorizing, or controlling the shipwreck of the panoptical project of modernism and the dilemma left for the architect to solve. Hejduk once said that when the physicians cured tuberculosis they deprived modern architecture of its best program. He accepts the modern imperative of program and is thus forever condemned to operate in the shadow of lost programs.

This becomes visible for perhaps the first time in the Cemetery for the Ashes of Thought, a key transitional project from 1975. Hejduk himself signals its decisive character when he says that it "is an absolute argument which everybody makes believe doesn't exist."19 It marks a threshold in the emotional territory of the work itself Again, he writes, "I suspect that in these last four years my architecture has passed from the 'architecture of optimism' to what could be defined as the 'architecture of pessimism.’"20

This key work extends, for perhaps the first time, the characteristic formal systematicity to the realm of the program and narrative. Hence it becomes an "art of approximation" that places in close proximity the concreteness of metric form and the immeasurable space of the word. Hejduk's laconic description deserves to be cited in full :

-

The Molino Stucky Building's exteriors are punted black. The Molino Stucky Building's interiors are painted white. The long extended walls of the Cemetery for the Ashes of Thought are black on one side and white on the other side. The top and end surfaces of the long extended walls are grey. Within the walls are one-font-square holes at eye level. Within each one-foot-square hole is placed a transparent cube containing ashes. Under each hole upon the wall there is a small bronze plaque indicating the title, and only the title, such as Remembrance of Things Past, The Counterfeiters, The Inferno, Paradise Lost, Moby Dick, etc. Upon the interior of the walls of the Mulinu Stocky Building are small plaques with the names of the authors of the work : Proust, Gide, Dante, Milton, Melville, etc. In the lagoon on a man-made island is a small house for the sole habitation of one individual for a limited period of time. Only one individual for a set period of time may inhabit the house, no others may be permitted to stay on the island during its occupation. The lone individual looks across the lagoon to the Cemetery for the Ashes of Thought.21

The author and work are unhinged : the space of the hook must be reconstructed in the time, space, and experience of the viewer. The cemetery is a place of mourning. It is the place that makes concrete the condition of loss. But it can also he a place for the positive exercise of memory. A place in which, by the traversing of — real or virtual — memory places, our active capacity for the construction of memory is restored.

Henceforth, Hejduk's architecture cannot be separated from program, from the written script. Hejduk begins to rethink the conventional notion that architecture's subject is an anonymous, faceless visitor. He begins to define the characters who will perform this script. These will later become more precise : The Inhabitant Who Refused to Participate, or in the Lancaster / Hanover Masque, The Bargeman, The Reaper, The Sower, and The Tolltaker In the case of the Molino Stucky project, description and inflection is embodied in the house itself, an extraordinary embellishment on the Wall Houses, whose plasticity stands as a foil to the stark serial restraint of the cemetery walls. The parallel structure of program and form creates a current of interpretive energy : "To every actual intensity belongs a virtual one."22

The Cemetery for the Ashes of Thought also marks a new articulation of theory and practice in Hejduk's work — perhaps even an inevitable outcome of the earlier critique of theory. In the work since 1976, Hejduk subverts the conventional theory / practice opposition by collapsing the discursive privilege of language into the project. Rather than holding apart text and project so that the text can be compared to the project as verification, or vice-versa, Hejduk's architecture begins to encompass the discursive itself, which now operates within the form of the project. Hejduk writes : "The drawing is like a sentence in a text, in which the word is a detail....a detail helps incorporate a thought."23 Hejduk thus reformulates the relationship between architecture and language which was so decisive in the theoretical discussions of the 1970s. Rather than appealing to the semiotic, and preserving the privilege of the linguistic over and above the architectural, Hejduk (operating according to the logic of "nothing but architecture,") incorporates literary practice directly into architectural practice. For Hejduk theory is not a foreign body or a parasite, but is instead a domain already properly architectural. This is a more complicated and ultimately problematic procedure. Hejduk wants to envelop and surround these other practices in the aura of the architectural. He echoes Le Corbusier : "It seems to me that architecture is radiated by the building and does not clothe it, that it is an aroma rather than a drapery; an integral part of it and not a shell."24

Therefore the "density" that Hejduk wants to achieve in his work exists neither in its formal opacity, nor in the weight of individual works, but in an incremental accumulation and tension between heterogeneous practices, figures, and thoughts. Density is created by the coextensivity and interaction of all these monadic entities, each competing for the same territory. These distinct practices improperly occupy the same ground. A complex spatiality results : a textual architecture that is the exact counterpart to the compositional tactics of Hejduk's projects; a textual architecture that necessitates a system of reading "inside and around this writing; a system capable of making each text the outside or absent center of another text. "25 This is the "untenable" position that Hejduk maintains with respect to the architecture / language debates of the 1970s : an extreme autonomy of parts which nonetheless display an uncanny, monadic interdependence.

Practice II (Section B) : "Little Mechanical Houses"

Project : Dilemma House

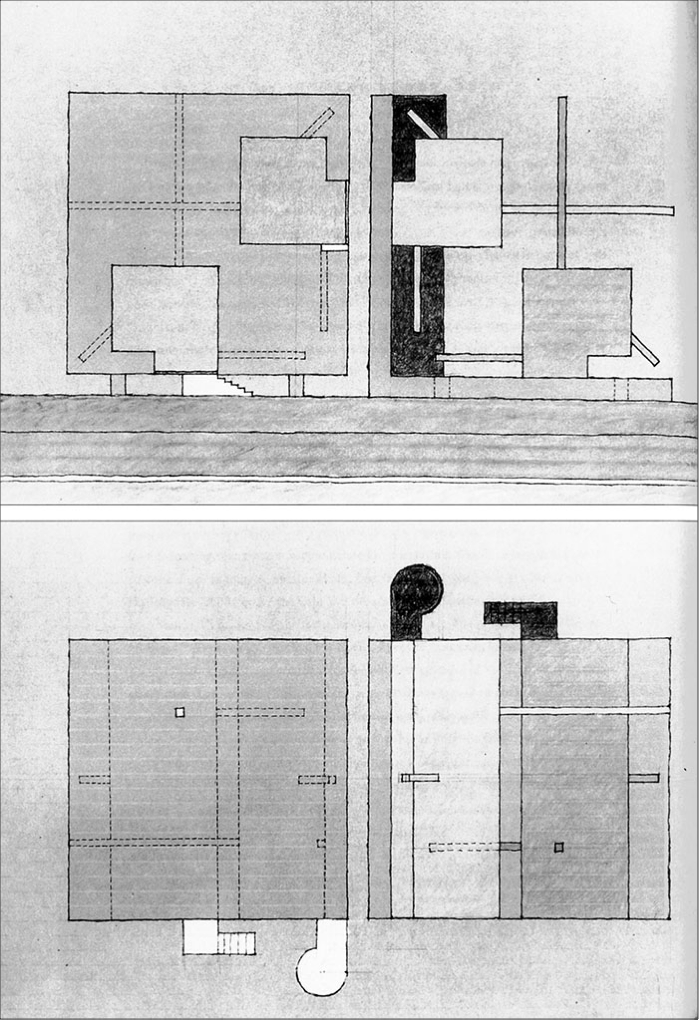

John Hejduk describes the Dilemma House (see illustration on p. 78) as "perhaps the most abstract I ever attempted," the culmination of a series of "little mechanical houses."26 The result of a simple but rigorous, and ultimately irreducible, series of formal moves, this exercise is emblematic of the formal research that was so evident in the Diamond Houses, in the One-Half and Three-Quarter Houses, but which, implicitly since the Wall Houses — which evoke a poetic of denied spaces and boundaries transgressed — and, explicitly, since the Cemetery for the Ashes of Thought, seems to have been left behind.

Beginning with a given cube, a volume is cut out, slid, rotated, and set down next to the original cube. A strict consistency is maintained. Note for example that the figure of the void formed by the suspended volume of the left side is the perfect mirror of the L-shaped figure that holds in place the volumes of the right hand. The visual necessity to lift up the solid off the ground is answered by cutouts in the base of the L that correspond exactly to the feet under the cube. The nature of the formal process should be noted as well : the void is cut out, slid and rotated, but then slid again, back into place. This is not an abstract projective operation, but a concrete series of operations, performed as if the elements were already material. Unlike the houses of Eisenman, where the building acts as a registration of abstract and complicated formal procedures, in Hejduk's work, form is the result of a series of simple and direct manipulations of the concrete elements of the form itself.27 For all its formal precision, this is not a geometrical operation, but rather a plastic operation. The stairs, the only elements not produced out of the formal procedures, confirm this. They are given elements, additive, abstract readymades, unaccountable and not subject to the exact rules that govern so precisely the other parts.

Two interrelated points seem worth emphasizing. First is the emblematic character that the geometry takes on. There is here a kind of emergent figuration, achieved through the formal play, which points in turn, to that which — despite the abstraction and formal freedom of the project — remains untouched. In order for the figure to be read, for the face to appear, the basic orthogonality of the cubic form must be maintained. Frontality and a reference to the planar coordinates of projection persist. Here, however, it is necessary to clarify what this might mean. Frontality is not evident in the facade — as a mask, as a singular face — but in the faces, the multiplication of frontality. As a formal idea, this has been present since the Wall Houses, and it becomes explicit with a project like the North South East West House, which presents the viewer four faces, each distinct but of exactly equivalent importance. To prefer one over the other, in this case, as in the Dilemma House, would be pointless. In contradistinction to the formal paradigms proposed by Colin Rowe (and reiterated by Kenneth Frampton28) each face establishes, through the rectilincarity of its geometry, a condition of frontality regardless of the viewer's position. Meaning, for Hejduk, resides primarily in the figural capacity of architecture. Here, the singular figure is multiplied, and the design effect is to heighten the possibilities for the production of meaning.

Hejduk's "abstract machines" produce the effect of faciality through operations and configurations that are not themselves reducible to resemblance, to the frontality of the single facade, to the mask, the "expressive" face. Faciality is located as much in the profile, in the sideways glance, as it is in the static formal view.29 It does not fix the gaze of the spectator in a "face-to-face" confrontation, but multiplies and redirects the gaze. "Do not expect the abstract machine to resemble what it produces" warn Deleuze and Guattari.30 The beauty of Hejduk's "little mechanical houses" is that they produce a whole series of effects, multiple, unpredictable, and unanticipated, which do not themselves resemble the mechanism of their production.

Postscript : "Sharpening the knife”31

We are flax in the field.

We lie in flat patches.

We are acted upon by the sun and bacteria — what are they called anyway ?

And to my right is a shelf of Tolstoy.

One of his words has been lying in this field with me for ten years. I'll check the passage.

-

I remember walking down the street once in Moscow and seeing a man step outside ahead of me and peer at the stones in the sidewalk; then he selected one stone, crouched over it and began (or so it seemed to me) to scrape and rob with singular strain and effort.

-

What is he doing to that sidewalk ? I thought. When I got right up to him, I saw what this man was doing. It was the young man from the butcher shop : he was sharpening the knife on a stone in the sidewalk. He had no thought for the stones at all, though he was scrutinizing them; still less was he thinking about them while performing his task — he was sharpening his knife. He had to sharpen his knife in order to cot meat; I had thought he was doing something to the stones in the sidewalk. In exactly the same way, man appears to be busy with commerce, treaties, wars, the arts, the sciences when one thing matters to him and that one thing is all he does: he is clarifying for himself the moral laws by which he lives.

I have nothing against the late Tolstoy. His art is what matters — and that's all.32

I want to end with this open question about the ethical dimension of Hejduk's architecture. Adolf Loos is said to have had a yardstick for measuring the architecture of a house : "Imagine a suicide in [that] room, don't you feel the atmosphere around a person who kills himself as a taunt ?" Perhaps only Hejduk, having sharpened the knife through forty years of practice would dare to make this particular incision. Beginning with the reductive perspective of "nothing but architecture," the work passes first through a stage of constraint, of narrowing, sharpening, the paradoxical consequence of which is to open up the definitions of both theory and practice. Hedjuk's exemplary practice allows us to see as already architectural a whole series of events and practices clustered around architecture's so-called margins.

1 Jean-Luc Godard, "Rien que le cinéma," Cahiers du Cinéma 68 (February 1957).

2 "We're born, you could say, appropriately ton late, because there's a lot of architects in my generation running around thinking they're masters. A generation before or two generations were masters, I mean real masters of architecture." John Hejduk, interview, A+U (January 1991).

3 Michel de Certeau, Heterologies : Discourse on the Other, Brian Massumi, trans. (Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press, 1986), 192.

4 Note for example Philip Johnson's pronouncement in Five Architects that "John Hejduk is... a theoretician's designer." Philip Johnson, "Postscript," in Five Architects (New York : Oxford University Press, 1975), 138.

This error persists. A 1995 New York Times article identifies Hedjuk as the "consummate paper architect, an artist who has shirked off the cumbersome apparatus of conventional practice..." Herbert Muschamp, "Fleeting Homage to an Architect Who Only Dreams," The New York Times (9 April 1995) : 40.

5 "In the nomad sciences, as in the royal sciences, we find the existence of a 'plane,' but not at all in the same way. The ground level plane of the Gothic journeyman is opposed to the metric plane of the architect, which is off site and on paper." Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, Brian Massumi, trans. (Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 368.

6 Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, Steven F. Rendall, trans. (Berkeley : University of California Press, 1986), 66.

7 Viktor Shklovsky Sentimental Journey, Richard Sheldon, trans. (Ithaca, NY : Cornell University Press, 1970), 233. A distinction must be drawn between the parallel advancement in the nineteenth century of aesthetic debates and technical practice (which of course had its own codes and disciplinary limits) and the theorization, in the early twentieth century, of these "peripheral" practices. Note, for example, the appeal to engineering practice in Le Corbusier's chapters in Towards a New Architecture on "Eyes which do not see." Le Corbusier upholds the classical position of theory : as the disciplinary agent that will name and categorize what appears unconsciously.

8 "Introduction," Five Architects, op. cit., 7.

9 John Hejduk, Mask of Medusa : Works 1947-1983 (New York : Rizzoli International, 1985), 129.

10 Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Kafka : Toward a Minor Literature, Dana Polan, trans. (Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press, 1986). Through the example of Kafka, the Czech Jew writing in German, Deleuze and Guattari develop the concept of a minor literature, the "deterrirorialization" from within of the dominant language: "A minor literature doesn't come from a minor language; it is rather that which a minority constructs within a major language." (p. 16) "The three characteristics of minor literature are the deterrirorialization of language, the connection of the individual to political immediacy, and the collective assemblage of enunciation." (p. 18).

11 George Steiner, "K," in Language and Silence : Essays on Language, Literature, and the Inhuman (New York : Atheneum, 1967), 126.

12 Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence : A Theory of Poetry (New York : Oxford University Press, 1973), 5.

13 Harold Bloom, A Map of Misreading (New York : Oxford University Press, 1975), 10.

14 Kafka, Diaries (15 December 1910), 33; cited in Deleuze and Guattari, Kafka, op. cit., 23.

15 To signal the appropriateness of Bloom's formulation over that of Deleuze and Guattari in the particular case of Hejduk is not to endorse in a general sense one theory over another. Of course, the heroic battling among Oedipal antagonists — as an interpretive figure doomed to failure, riddled with negativity, and burdened with its own interiority — is exactly the target of Deleuze and Guattari in The Anti-Oedipus. I think it is possible (without appealing to discredited notions of influence and iutentionality), to map out an interpretive territory both productive and appropriate to an individual architect, based on a knowledge of the milieus in which he works, the tastes, the likes, dislikes, and parauoias that structure his intellectual life. In the ease of Hejduk therefore, I will make a case for an old-fashioned modernism, rooted in the New Criticism in literature, prewar European modernism in painting; the modernisms of Mondrian, Klee, of Gide, Proust, Robbe-Grillet.

16 For the distinction between "autographic" and "allographic" practices, see Nelson Goodman's discussion of notation in Languages of Art; An Approach to a Theory of Symbols (Indianapolis : Bobbs-Merrill, 1968).

17 Hejduk, Mask of Medusa, op. cit., 129.

18 "Section A"; "Section B" : these refer to designations in the organizational schema of Hejduk's book. Both the Cemetery for the Ashes of Thought and the Dilemma House fall into "Frame 5 : 1974-1979"; Section A encompasses the "literary" or "programmatic" works at the urban scale — Silent Witnesses, 13 Watchtowers for Cannaregio, New Town for the New Orthodox, while Section B includes projects of a more "architectural" character — domestic-scale exercises of descriptive geometry, abstraction, and projection: the Dilemma House, North South East West House, etc.

19 Hejduk, Mask of Medusa, op. cit., 135.

20 10 immagini per Venezia, 1975; cited by Rafael Moneo in "The Work of John Hejduk or the Passion to Teach," in Lotus 27 (1980).

21 Hejduk, Mask of Medusa, op. cit., 80.

22 Brian Massumi, A User's Guide to Capitalism and Schizophrenia : Deviations from Deleuze and Guattari (Cambridge : The MIT Press, 1992), 66.

23 John Hejduk, "On the Drawings," in Lancaster / Hanover Masque (London : Architectural Association; New York : Princeton Architectural Press, 1992).

24 Le Corbusier, "Concerning Architecture and its Significance" from Almanach de l'architecture moderne (Paris : 1926), 138; cited in Larissa A. Zhadova, Malevich : Suprematism and Revolution in Russian Art, 1910-1930 (London: Thames and Hudson, 1982), 97.

25 Philippe Sollers, Writing and the Experience of Limits, Philip Barnard with David Hayman, trans. (New York : Columbia University Press, 1983), 127.

26 Hejduk, Mask of Medusa, op. cit., 89.

27 Appealing to the categories of Charles Sanders Peirce, it might be possible to characterize Eisenman's work as primarily "indexical" in nature, while Hejduk's mechanisms tend toward the "iconic." See the essay "Logic as Semiotic" in Philosphical Writings of Peirce (New York : Dover Publications, 1955).

28 See Rowe and Slutzky "Transparency, Literal and Phenomenal" and Frampton, "Frontality vs. Rotation" in Five Architects, op. cit.

29 "A missionary blamed his African flock for walking around with no clothes on." "And what about yourself ?" they pointed to his visage, "are not you, too, somewhere naked ?" "Well, but it is my face." "Yet in us," retorted the natives, "everywhere it is face." Cited by Roman Jakobson, "Linguistics and Poetics," in Languages and Literature (Cambridge : Harvard University Press, 1987) : 93 For the concept of faciality see Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, op. cit., 167-191

30 Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, op. cit., 168.

31 "I love history, I like to read books and everything else. But there's very little to offer when you are cutting a path through some kind of a jongle. It may tell you how to sharpen your knife, but that's it." Hejduk, Interview, A+U, op. cit. Somewhere — I wrote it down but never found the source — Paul de Man writes that "history is like a passage — you have to walk through it, but it tells you nothing about the art of walking."

32 VOICE OF A SEMIPROCESSED COMMODITY Viktor Shklovsky in Third Factory, Richard Sheldon, ed. and trans. (Ann Arbor, MI : Ardis, 1977), 22-23.

"Dilemma House," Elevation, Section, and Plan, 1976.

Ink and pastel on corrugated cardboard, 9 x 12 in.

Collection of the Architect. Courtesy John Hejduk, Architect.