ME, MYSELF, AND I

Peggy Dreamer

I approached the task of writing on John Hejduk with enthusiasm. Not only did I feel an affinity for the work, but, having been a student of Hejduk's at The Cooper Union, I thought I would surely have the advantage of being an "initiate." But two things became readily apparent. The first was the phenomenon of a critical displacement. The initiation factor with Hejduk was too strong, not just for me, but, as I began to realize, for critics and writers in general. One's initiation was accomplished by having the good sense to supplement the poetics with more of the same; exclusion came when one became gauche enough to analyze the poetry. It is interesting and not surprising to see how few critics have opted for the second route. This second phenomenon, though related to the first, marked an impossibility — not merely for me, although I am clearly including myself — of disengaging the work from the man. How strange, but not fortuitous, that someone like Hejduk, who seems at all cost to have avoided the commodification of his persona, should so strongly insert his person into the critical discourse. The writings surrounding the work have inadvertently directed attention to the mystery of the author "himself" Ironically, the work — so clearly innovational — has demanded that the critic retreat to the most archaic of critical forms : concern for authorial intent. There is a way in which, by the very overdetermination of meaning in the work, Hejduk has guaranteed for his own work a poverty of critical discourse.

In an attempt to understand the first phenomenon — the displacement of critical space — I shall focus on the second — the dominant presence of the author. The authorial presence might point to more deeply rooted concepts in the work. That is to say, Hejduk's own interjection into both the texts and the discourse about them might be understood not merely as an appendage to the work, but as an indication of the works' structural nature. In what follows, I shall examine the work in this light, as a form of "autobiography."

To call the oeuvre autobiographical is to say very little. To suggest that Hejduk is mining his own thoughts, memories, and obsessions as source material for his architecture is no revelation. But it interested me to see how the identification of Hejduk's work as autobiography points to structural conditions that shed light on how it functions within the discipline of architecture. I am interested here in the texts, particularly Vladivostok, not only because Ibelieve that they best represent the oeuvre, but because I don't think it is incidental to Hejduk as author that he privileges the literary format.

The four main conditions of autobiography explored here are : 1) the problem of the "I"; 2) the moral / ideological implications of this "I"; 3) the language of the "I"; and, 4) the role of the critic / reader.1 The first structural condition, having to do with the notion of "I" inherent in the autobiographical work, examines a "self" that is characterized by ontological ambivalence and structural narcissism. The ontological ambivalence of the "I" is best understood as a series of dualities : the subject and the object of the discourse; past and present "I"; the content and creator of the narrative. These dualisms are in turn unbalanced by the binary condition of the creator, in which the authorHejduk the man-is distinct from the authorial voice-the narrator.2 The "I" in autobiography is constituted in three ways : as author (present in the form of the work), as narrator (present in the style of its presentation), and as hero (or, the subject / content of the work).

I'd like to begin with the author. The author of the autobiographical text is a figure whose presence is felt but never directly perceived; a figure whose functional absence from the very scene that s/he has created only contributes to the authorial mystique. In Hejduk's case, this absent figure dominates not only the size of the void, but the precision of its placement. Hejduk abandons us in order to make us aware of our dependence on him. He is not willing to guide us through a text that might explain why we, the reader, will be shown Vladivostok or Lake Bakail; or why we are looking at photographs of Berlin and London and Philadelphia when our guidebook indicates we are in Riga.3

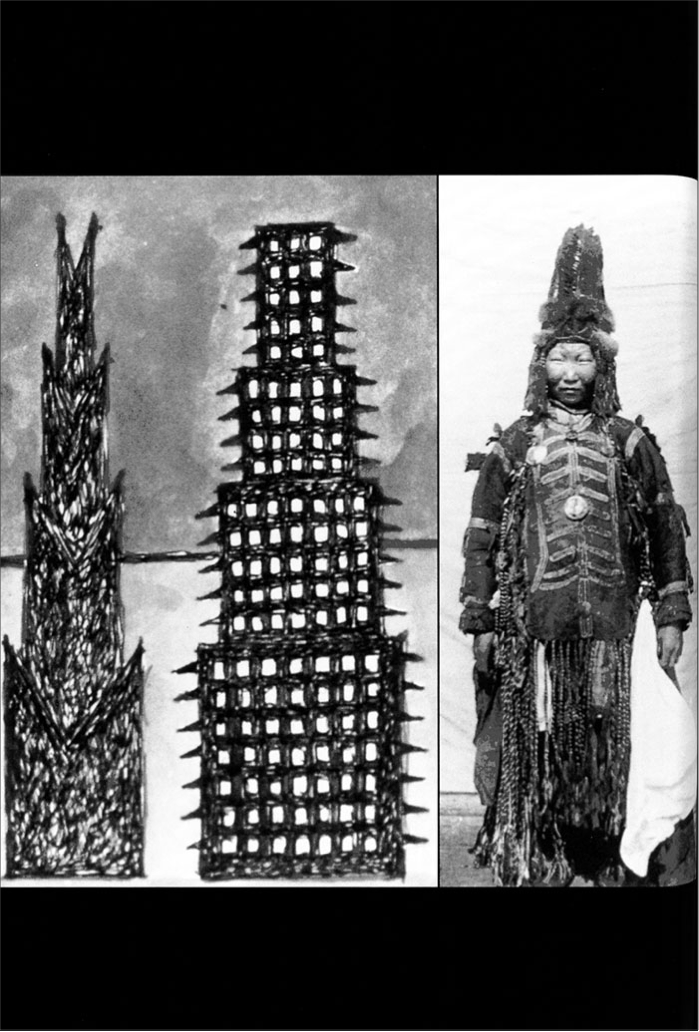

The narrator, the second self of the autobiographer, is the person who says, as in Greek drama, "We have to contemplate this," or "You should look here." But, as Roland Barthes has pointed out, this autobiographer is not responsible for the creation of the narrative itself. In primitive societies, for example, the responsibility for the production of a narrative was never taken by a person or an "author" but by a mediator or a shaman whose performance, but never whose genius, was admired.4 In Hejduk's case, this narrator / shaman is the tour guide, the person who picks you up at the train station and, as you move from city to city, shows you this, reports on that, tells you what such and such is made of, and who lives there. The distinction in Hejduk's texts between the narrator / shaman — direct, blunt, non-judgmental, catholic — and the author — opaque, precise, paranoid, and Catholic — (a distinction reinforced by the fact that the narrator has surely "been" to these places while Hejduk, the author, has not) is one of the notable features of Hejduk's work. It is the deceptively simple presence of the narrator fronting for the author that simultaneously hides him and draws attention to his authority.

Finally, there is the hero, the "I" of the autobiographical narrative, the character who performs the actions and thinks the thoughts, the hero who, for all her/his linguistic association with the author, is a wholly fabricated entity. In Hejduk's case, there are multiple heroes comprising one larger persona that forms the alter-ego of Hejduk himself.5 These heroes are the anthropomorphic buildings that are portrayed in the text, the Cemetery for the Mothers of the Children, the Garden of the Angels, the Masque, the Clock / Collapse of Time, etc.

In this autobiographical hail of mirrors, the heroes personify not only the author, but the narrator as well. Like the author — John Hejduk — these heroes are bulky and awkward; their hair is out of control. These personalities are closed and defensive; opaque and unforgiving; they prescribe and enact rituals; they read and write texts. Like the narrator, these heroes are tourists and shamans whose identities are not determined by the community they inhabit but are instead fixed by their own physical and spiritual itinerary; they are the "other" whose foreign character threatens the society. Beyond this double reference to the autobiographical creator, these heroes also more and more frequently refer to themselves. The explanation of their ability to multiply falls somewhere between the mythical gods (or the Virgin Mary) who produce offspring without sexual intercourse and the incestuous family that needs not look beyond its own clan for reproduction.

As was mentioned, the autobiographical "I" is characterized not only by ambivalence, but by a structural narcissism, a psychoanalytic selfinspection. What has been described as "the little extra privacy" provided by the autobiographical work over other texts, is in fact the invitation to dissect the author's (and the narrator's and the heroes') inner world.6 Hejduk, who is described by Daniel Libeskind as a "masterbuilder of metonymical distortions and lexical fictions," is, in this sense, the prototypical analysand. Hejduk's admission that "all speech is confession" — while subsuming the role of the analyst into that of the priest — confirms his interest in the inwardly motivated search.7 Admitting of sexuality and death, this confession/session is interesting not only autobiographically — because it exposes a Pandora's box of psychotic material — but because it demonstrates that sexuality, gender, babies, and old age are topics open for discussion in the discipline of architecture.

The Hejdukian narrator, too, has a psychological dimension, and her/his province, the style of the storytelling, demonstrates its own form of neurosis. Like the psychoanalytic imagination, the format of the storytelling is one of swimming images that depict not a real world, but a dream world. Logic and temporality are replaced by a taxonomy of obsessions whose two main characteristics are repetition and the transformation of facts into artifacts. Repetition is the economy of narcissism and repression: narcissism because the self, as Narcissus realized, can never break the chain of self-referentiality for fear of discovering its own irrelevance;8 and repetition because the always hidden becomes the always there.9 In Hejduk's work, repetition almost single-handedly structures the reading experience. Facts-as-artifacts — the turning of events into chronologically and spatially decontext ualized objects10 — organizes psychic events as a museum : myth and not morphology is maintained. In Vladivostok and the Mask of Medusa, the narrative presentation shows that, as in mythology and psychoanalysis, following after doesn't necessarily mean following from.

Hejduk's objects, his heroes, are also products of this narcissistic agenda. If the psychoanalytic urge is inwardly motivated, its effect is outwardly directed. The objectification of self, the urge to thwart morality by solidifying the life into an object, is a fact of both psychosis and autobiography.11 In the cross-fertilization between the inner and the outer worlds, each acts as a representation to the other. If Hejduk is the prototypical analysand, his heroes form the prototypical analytic landscape: the train journey; the rough and smooth houses; the isolated, singular aperture; and the interest in the number three all speak of double meanings eagerly awaiting analysis.12 Moreover, they also reenact, by the consistent cross-referencing of the inhabitant / subject with the building / object, the process of self-objectification at play in the autobiographical process in general.

The second structural condition of the autobiographical text has to do with the moral / ideological dimension. This is an issue raised immediately by the "me," the less secure version of the "I" that asks "how is the 'me' pertinent to you, to others ?" Two similar but distinct questions are embedded here : is this "me" universal, and is this "me" exemplary ? A Freudian interpretation of psychological activity assures a positive answer to the first. We all might have different neuroses and obsessions, but they are all caused by the same fundamental conditions : the obsession with death and Eros. This latter — the locus of the moral / ideological dilemma — is more complex. The author must satisfy the requirement that the life under consideration be reconstructed as an aesthetic whole at the same time that s/he must ensure that the necessary distortions of this life are not merely aesthetically motivated. If the autobiography is significantly different from the diary in rejecting a merely linear description of life's events, it retains its moral connection with the confession. For all autobiographical writers, and certainly for Hejduk, the style of the writing strives to respond to St. Augustine's warning (in his own autobiography) not to take pleasure in hearing a sermon when one is supposed to be listening to the moral message.13 The stylistic surface of the work necessarily takes on a disturbing, selfeffacing, quality.14 In Hejduk's work we can see the fear of producing work that might be appreciated on formal grounds alone, and hence the change from his early work is characterized by a deflection of the possibility of its aesthetic consumption.

But this morality does not function in a cultural vacuum; the instructions, exhortations, and rationalizations offered in the text are part of a social performance.15 As Barthes has pointed out, the miracle of the narcissistic activity of writing is that it has always provoked "an interrogation of the world."16 And just as the author discovers the world in her/himself, s/he ensures that the presentation of the life satisfies not only personal criteria, but social ones as well. In this light, the making of biographical fact into mythical artifact functions as a cultural communiqué and makes for cultural cohesion. The shaman is, after all, a community spokesman.

Hejduk's texts make apparent this intrinsic ideological concern-one that for Hejduk sits somewhere bttween a universalized mythical culture and specific politico-economic societies (as American, looking at European, Eastern European, and Russian cultures). It has been said that Europeans understand the ideological dimensions of the self more than do Americans,17 and in this sense one can understand the appeal that Hejduk makes to and has for a European audience. On the other hand, it must be added, the side of this ideology that is more moral than political, more mythical than social, ultimately brands him as American. The buildings themselves, Hejduk's heroes, symbolize the bounded relationship of the individual to the social. It is one of the peculiarities of Hejduk's subjects and objects that, despite their specific histories and idiosyncratic resumes, they have no private identities. They function as institutions whose fated rituals and repeated itineraries perform cultural, not personal, duties.

The third structural condition of autobiography is the relationship of author to language. In this, the issue of Hejduk's work is clearly more complicated than in the literary situation, because the "language" here is made up of a number of visual mediums and a range of textual objects. While I want to acknowledge the pitfalls of applying strictly literary formulations to non-literary work, it seems worth pointing out that certain attitudes taken by an author to her / his "language" cross boundaries of medium and discipline.

Speaking generally about writing and not merely about autobiographical writing, Barthes points out that authors, as opposed to writers, labor on language in two ways : as technical labor (composition and style) and as artisanal labor (patience, correctness, perfection).18 Barthes suggests that in the most extreme form of this labor the author loses her/his identity in language and a tension is set up between author and language.19 This view of the author is clearly applicable to Hejduk, whose labor in the language of architecture is both obsessive and transcendent.

The autobiographical author, then, exacerbates the preexistent tension between the author and the language. Given the autobiographer's self-alienation she/he must refer to her/himself in an allegorical way, and is dependent on the language's capacity to structure metaphor. The surrogate self is a trope, a figure of speech, a formal configuration of language.20 Indeed, the autobiographer's relationship with her/his language is more desperate than the above image of "labor in language" implies : the autobiographer depends on language because the shape of the life under consideration is only established in the act of constructing it. The language of the autobiographer constitutes and sustains an identity that does not preexist the act of composition. The proper probing of the language is equated with the properly shaped self and it becomes impossible to approach either casually. In Hejduk's work, there is a sense in which the precision of the narrational construct, like the precision of the heroes' formal identity, is a matter of life or death; the wrong move is equated with a mortal wound. This is formalism in the most profound sense of the term, in which form is not merely an aspect of aestheticization, but of identity.

The fourth and final structural condition of the autobiographical act is the realignment of the reader's and critic's role, a condition that leads us back to the originally suspended question of critical displacement occasioned by Hejduk's work. I want to suggest that the autobiographical text insulates the author and privileges the reader at the expense of the critic, not because the birth of the reader that Barthes suggests accompanies the "death of the author," but because the autobiographical author, both absent and present, is absolutely hermetic. The author, having looked with due detachment at her/his life, aims to both convey and exemplify the judgments this scrutiny has afforded.21 The reflections have taken on the status of criticism; criticism has become one with the mode of viewing self. The author not only usurps the critic's territory, but also shrouds her/himself in a veil of authenticity that is difficult to assail.

The reader, on the other hand — the person, who despite the moral inquiry at the heart of the text, looks to be less judge than accessory — is reconstituted as accomplice. Using sincerity as a principal stylistic device, the author seduces the reader by privileging her/him with the most intimate of confidences. And the reader, thus honored, becomes the willing cohort. Indeed, the reader can be said to justify the writing, providing not only the reason for its occurrence, but supplying it with the double perspective at the heart of the autobiographical inquiry. In this sense, the reader is structurally built into the text. The unity of the book, then, is provided by the destination — the reader — and not the originthe author. In this, the critic is swindled twice over. Not only is s/he denied a vantage point from which to gain particularly privileged information, but, once operating in the general domain of readership, the critic functions only from the accomplice's point of view. Thus the seduction of the reader is ultimately the victimization of the critic, who, like the viewer of Medusa, is incriminated just for looking.

The above, motivated by an attempt to establish a critical position vis-à-vis Hejduk's work, has left little time or space to examine the relationship of this work to practice. But examining Hejduk's work as autobiography has implications for making such an evaluation. First, with regard to the narcissism of the search for self, it should be noted that this does not imply that one should view this work, as has been the case with autobiography in general, as "the feast that starves the guest."22 What is being presented here is the possibility that architecture might function not on the traditional axis of architectural meaning — building to user — but on an alternate axis of "me" and "you." Hejduk reminds us that this "you" and this "me" possess gender, age, and sexuality. Moreover, because the author of an architectural work is not "dead," and because buildings do not spring up autonomously, he intimates that one must take responsibility for all these manifestations of the self In this scenario, the language, the architecture, and the buildings aren't relegated to a secondary position as much as they are examined for what constitutes an "architectural me" and an "architectural you."

But if we acknowledge that this feast might actually feed its guests, we do not want to say, as Libeskind might, that Hejduk's "masque" architecture is to other architecture "as a meal is to a menu." Libeskind suggests that if we all had the sensitivity and the insight, we, too, would be serving up the "real thing"; he offers it as a paradigm to be imitated. I am suggesting that just as autobiography is its own genre, Hejduk's work is, too.23 Both function as metacritiques of the act of authorship, and not as examples of authorship. And just as not everybody should be authoring metacritiques instead of texts, not all architects should be producing masques instead of buildings. Hejduk's work serves as a reminder to architects that there is a "me" that makes buildings. He doesn't show us how to make them. (In this regard, any discussion of Hejduk as an urban planner or comparisons to Rossi are, I feel, misdirected.)

The second condition of morality expands the first. In reminding us that there is no divorce between who we are and what we do, Hejduk is not assuming, as is normally the case, that by making responsible buildings we become responsible citizens. Rather, first and foremost, he is emphasizing that we should be responsible citizens. His pessimism is less a pessimism about the cultural situation in which his buildings / heroes operate as much as it is a pessimism about the possibility of structuring the citizen who can withstand the knowledge of her/his own structural limits.

The third condition of the attachment to language only reiterates this point. Barthes has written that "an author's responsibility is to support literature as a failed commitment, as a Mosaic glance at the Promised Land of the real."24 Hejduk has taken on precisely this responsibility in architecture. What architecture takes to be "the real," though, is clearly less abstract than what literature takes to be "real"; while both speak of culture, architecture participates in a more physical, and therefore more directly political, arena. Hejduk then has taken on the responsibility of supporting architecture as a failed political commitment. His work is a mapping of both this fact and the frustration it engenders.

The fourth condition of the readjusted role of the critic only brings us back to the issue at hand. In this specific instance, only the admiration of someone who must, at this point, prove to be a non-initiate can be put forward.

1 In this paper, the material on the theory of autobiography is drawn from the following sources. Specific footnotes will be given only when the idea is particular to a single text.

-

-

mutlo konuk biasing, The Art of Life : Studies in American Autobiographical Literature (Austin : University of Texas Press, 1977).

-

irving louis horowitz, "Autobiography and the Presentation of Self for Social Immorality," New Literary History vol. 9/1 (Autumn 1977).

-

roy pascal, Design and Truth in Autobiography (Cambridge : Harvard University Press, 1960).

-

john pilling, Autobiography and Imagination (London : Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1981).

-

louis renza, "The Veto of the Imagination : A Theory of Autobiography," New Literary History vol. 9/1 (Autumn 1977).

-

jean starobinski, "The Style of Autobiography," New Literary History vol. 9/1 (Autumn 1977).

-

john sturrock, "The New Model Autobiography," New Literary History vol. 9/1 (Autumn 1977).

2 This idea of a narrator (represented by the style of the text) as distinct from the author (represented by the form of the text) is developed by blasing, The Art of Life, op. cit. : xxi.

3 These names refer to the locations of Hejduk's projects, both real and imaginary, as well as the major and minor headings of Vladivostok.

4 roland barthes, "The Death of the Author," Image Music Text, Stephen Heath, trans. (New York : Hill and Wang, 1977).

5 Here, the Kleinian notion of the "split ego" that metaphorically represents itself in numerous and conflicting selves comes immediately to mind.

6 sturrock, "The New Model Autobiography," op. cit. : 54

7 Here surely, it must be added, lies the affinity of Hejduk to the interview format, as witnessed in Mask of Medusa and a number of other publications. Not only does it demonstrate the structural condition of both the confession and the analytic session but, in as much as there is never an interrogator that is hostile to or "other than" Hejduk, the bifurcated ego that is the structural condition of autobiography.

8 blasing, The Art of Life, op. cit., xxi.

9 The idea of repetition as it relates to repression is discussed in an unpublished paper by Mark Rakatansky and draws on ideas developed by Catherine Ingraham.

10 renza, "The Veto of the Imagination," op. cit. : 2.

11 pilling discusses the underlying urge of "objectification" inherent in autobiography, taking his ideas from the autobiographical work of adrian stokes and this author's engagement with the psychoanalytic work of melanie klein.

12 sigmund freud, "The Symbolism of Dreams," Introductory Lectures of Psychoanalysis, James Strachey, trans. (New York : WW Norton and Co., 1966), 149-169.

13 starobinski, "The Style of Autobiography," op. Cit.: 296.

14 pilling discusses the consistently difficult "surface" of the autobiography, but doesn't link it to the moral issue.

15 horowitz, "Autobiography and the Presentation of Self," op. cit. : 173. horowitz in his article also refers to renza, who was the first to point out the ideological dimension of the self as developed in autobiography.

16 barthes, "Authors and Writers," in Critical Essays, Richard Howard, trans. (Evanston, IL : Northwestern University Press, 1972,) 144-145. Barthes writes : "By enclosing himself in the how to write [emphasis his], the author ultimately discovers the open question par excellence : why the world ?"

17 horowitz, "Autobiography and the Presentation of Self," op. cit. : 175.

18 barthes, "Authors and Writers," op. cit., 144

19 This loss of identity is Barthes's famous "death of the author." I would only argue that this intense working of the language inevitably bares the imprint of the manipulating "I," so that in nonautobingraphical as well as autobiographical texts, the "I" can never disappear. Indeed, the Russian Formalists have shown that the essence of good literature — its "form" — is a certain self-consciousness that prevents the reader from forgetting that the text is manipulated by the author. This is an important point to make if one is going to insist, as I am, that the stronger one's engagement is with the language, the stronger the form and the stronger one's authorial identity.

20 renza, "The Veto of the Imagination," op. cit. : 15. To see the self as a "figure of speech" points to the particularly bodily aspect of language, where the "figure" of rhetoric was originally associated with the physical gestures of the body. In this, language does share with architecture, whose proportions appeal to physical and empathetic anthropomorphism, a link to the human body. The particularly anthropomorphic quality of Hejduk's architecture as well as his affinity for rhetorical language makes his work a good example of this bodily truss-fertilization. See Peggy Deamer, "Subject Object Text," in Andrea Kahn, ed., Drawing Building Text (New York : Princeton Architectural Press, 1990).

21 pilling makes this point in his discussion about Henry James, in Autobiography and Imagination, op. cit., 27.

22 guy davenport, as quoted in Horowitz, "Autobiography and the Presentation of Self," op. cit. : 175.

23 The suggestion that autobiography is its own genre is not universally shared, but is particularly promoted by Renza ("The Veto of the Imagination," op. cit. : 4), who wants to see autobiography in terms of its particular stylistic distinctions.

24 barthes, "Authors and Writers," op. cit., 146. Barthes also writes, in a passage that seems particularly applicable to Hejduk, "Language neutralizes the true and the false. But what the author gains is the power to disturb the world."

"Office Buildings," from Vladivostok, e. 1987.

Ink and watercolor on Japanese rice paper, 5 x 7 in.

Collection of the Architect. Courtesy John Hejduk, Architect.

Shaman from Joan Halifax, Shaman : The Wounded Healer (London : Thames and Hudson, 1982).