THE NATURE THEATRE OF JOHN HEJDUK

Edward Mitchell

The current political climate has complicated the means to fix borders. The old world order that was dominated by two superpowers has now begun to disintegrate into tribal factions, while the countermovement of economic multinationalism has erased the state and has rewritten the city at the center of the issues that define this now fluid period of contemporary history. No longer conditioned or defined by physical proximity, cities have themselves been affected by the fluidity of borders. Using John Hejduk's Vladivostok, which is often read as a frame delimited by a set of individual pieces and characters, I want to suggest that the city or the urban performs instead as an energized network. Invoking the language of Cilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, I want to suggest that, despite the fact that the urban infrastructure still remains, urbanism might today be best considered as a measure or degree of intensity, a rate of energy flow, or a frequency of events.

Any interpretation of Hejduk's work forces the critic to play the role of an angel who must wrestle with an old demon — architectural form. While Colin Rowe was able to separate Hejduk's Morale / Word from its Physique / Form, most Hejduk criticism continues to connect the two, labeling form as either radical or conservative. Despite the work's attachment to the persona of Hejduk, this connection is not easily named. The inability to name this connection, however, has not so much to do with Hejduk's work, but with the inadequacy of customary definitions of the political. Instead of reattaching meaning to matter, it is possible that there exists a situation in which a "connection between support and ornament replaces the matter-form dialectic."1 It becomes difficult, however, to pin Vladivostok with meaningful form. What Twill do instead is attempt to locate a more dynamic system of singularities or energy levels that constitute a network of angelic exchange.

Just as angelic annunciation delivers the word unto base matter J, as critic, am scripted to enlighten Hejduk's murky world through language, giving it a universal set of principles that might be used as an urban model. The relay of the traditional angelic message, "Have faith," is, by nature, contradictory. It delimits the possibility of doubt and the potential of undecideability, distinguishing for the first time between the realm of heaven and earth. Though this message deterritorializes the unity of the world, it circles back, and reterritorializes a hierarchy based on meaning. The deliverance of divine messages denigrates the world of materiality — flesh appears as weakness and meaning embodied in form is privileged over matter. Knowledge stratifies space with the placement of angelic border creatures positioned as mediators. But because they are quasi-divine creatures — and internally conflicted — the angels know that the word cannot be believed. They hesitate when they speak and delay their entry. Thus situated in this hesitant state between heaven and earth, the angels serve as a gauge between transcendency and base matter, between expressions of faith and doubt. Similarly, as a network component, the angels operate as a delay to meaningful description of form and, therefore, to the establishment of boundaries.

Rather than ask what the angels mean, we should interrogate their actions. As only a poor imitation of an angel — a prop both ornamental and excessive to Hejduk's work — I am like one of the mummers at the racetrack / recruiting station at the Nature Theater of Oklahoma, in Franz Kafka's novel Amerika. While Kafka's angels trumpeted the fanfare, "Everyone is Welcome !," I must warn you that entry into Hejduk's work is difficult-not because it is impenetrable, but because a point of entry is structurally denied by the work itself. Both Kafka's Nature Theater of Oklahoma, which travels through Amerika, and Hejduk's carnival of masques, which drifts through Vladivostok, offer potential programs for a mobile theater of events without fixed boundaries. While the former old world order of American / Soviet opposition formed ideological borders with points of entry, Amerika / Vladivostok offers instead degrees of urbanism that form a continuum along which the urbanistic thresholds are marked by vectoral becomings. In the old world order, angels — creatures of the threshold — wait suspiciously outside the door with their divine messages; but, in a network they cannot be confined to a single entry point or single meaning. Instead, angelic exchange proliferates throughout the entire network.

The program of the Nature Theater is angelic. In Vladivostok, angels serve as intervals between the definitions and the images of the masques. Whether these agents of mediation are called actors, as in Kafka, or angels, as in Hejduk, their respective "theaters" form networks whose citizens / subjects are constantly called into question and repositioned. In some respects both Kafka's and Hejduk's Nature Theaters, and their components - Kafka's bureaucratic machines like the Castle and the Law Court, and Hejduk's angels — operate like recent software programs that use demons, actors, or servants as tools for modeling decentralized systems of artificial intelligence. Hejduk's masques, which carry their own information and reform themselves within any given assemblage and locale, are independent of specific site or occupant.

Precisely because it constitutes a properly named point of resistance to the inclusive format of the network, I choose to enter Vladivostok through the House of the Inhabitant Who Refused to Participate. Vladivostok's urbanism takes the form of a series of random events scattered within the pages of the book. Refusal to participate defines the excluded position outside the bounded set of terms that delimits the territory of Vladivostok. The house is composed of four major elements: the house itself, twelve 6' x 6' x 9' cells suspended from a wall facing onto a piazza with circulation on the opposing side; a 6' x 6' x 72' stone tower; a 3' x 6' x 6' deep hole in the campo; and a set of bleachers. Eleven of the twelve cells of the house contain functional apparatus, such as furniture and plumbing fixtures, mobilier and conduits. The twelfth cell, number 7, is empty. Hejduk describes the relationship of the pieces.

-

At the exact level of the Participant of Refusal's empty cell there is affixed upon the campo tower a mirror, the precise elevation size of the opposite cell. When the inhabitant of the house stands in his empty room he simply reflects himself upon the mirror of the opposite tower.

-

Any citizen is permitted to climb the ladder and enter the stone tower. Once in the tower the citizen can see the lone inhabitant across the campo within his cell. The citizen can observe without being observed.

-

There is only one risk for the hidden observer. Another citizen may release the overhead tower door consequently enclosing within the tower the citizen observer.

Architecture is limited to a minimal condition of inhabitation, with the functional spaces of the house displayed in rational order on the wall surface facing the campo. But, despite its aesthetic continuity with modernist precedents, the house cannot be reduced to pure function. While eleven of the twelve identical rooms are cells of minimum existence containing the mobile functional elements of furniture and plumbing, the seventh cell creates an excessive condition, marked by its lack of autonomous function relative to the house itself. It is neither self-evident nor self-referential. While for the eleven other cells form fits function, more or less, there is no form proper to the voided space, nor a function compatible with its lack of form. It is excessive precisely because of its lack. The seventh cell operates critically in two ways. First, it holds the place of the void within the campo, and secondly, it uses the void to refer outside of itself, accessing a virtuality beyond its physical boundary as it aligns the mirror to the tower window. The architectural types of bleacher, tower, wall house, and pit are reformulated into a typology of visibility.

The House of the Inhabitant Who Refused to Participate continues Hejduk's obsession with the problems of vision and surface that began not only with the early Diamond Houses, which collapsed the illusionary space of the isometric drawing onto the flatness of the page, but with the earlier Wall Houses, which negotiate between two- and three-dimensional territories. While the Wall Houses marked an actual physical division, the mirror on the tower sutures the space of the Inhabitant Who Refused within visibility, turning the real plane of the wall into the virtual plane of the mirror. Hejduk has set up a two-sided image, using the mirror as the plane of negotiation, where each side exchanges properties across its surface. The scene of the campo even dispenses with the surface to focus attention on the gaze itself.

Unlike the classical mirroring object that returns the image of the subject to itself, thereby reaffirming it as monad, in the House of the Inhabitant Who Refused to Participate, the mirror exchange does not reflect an equivalent representational form. Instead, the arrangement of objects activates a circuitous network of relations wherein each object returns the gaze of the other. Opened by the voided space of the seventh cell, vision becomes its own trap for the inhabitant Who Refused to Participate. The mirror tower thus acts as a relay station rather than as an architectural monument.

According to the script, the inhabitant sees his own reflection at the beginning of the circuit. His signifying presence is reproduced as a political poster on the tower wall, thereby activating the static space of the city. The Inhabitant's refusal to participate is contradicted, however, by his representation within the civic square. He cannot refuse to participate if he occupies the seventh cell, thereby surrendering his proper identity. Presence becomes its own trap; and yet this is also unavoidable for all involved. Alternatively, the seventh cell seemingly must remain unoccupied so that the mask of the mirror is able to serve as a convincing disguise for the citizen / observer who also plays the role of non-participant outside the boundary of the house. Because of the angles of reflection, the proper identity of the Inhabitant can only be verified by the tower occupant who must double the role of the One Who Refused. The mirror thus acts as a mask for the citizen / observer. If he can verify the presence of an Inhabitant Who Refused, it becomes a case of mistaken identity. On the other hand, if he sees no one, he cannot verify the possibility of a position of refusal for the participant although he now wears the mask of refusal himself. Refusal to participate in this network of representation is signified by an absence or marked by the absence of a verifiable signifier.

To resolve the logical paradox proposed by the rigid dichotomy of absolute presence or absence, the house must operate as a network component oscillating between the two conditions. Put simply, the house measures degrees of becoming. Without need of the physical body, the seventh cell anticipates and contains the function of the subject by operating within a field of visibility rather than as a point of view. The gaze situated in the objects of the campo precedes the subject while it marks the presence of the subject within the grid of the campo's surface. The encroaching sense of paranoia engendered in the subject and enhanced by the presence of the grave-like pit and the door that seals up the tower like a crypt, is the functional remainder of the mathematics of the gaze.

The exchange of zero for one in seventh cell of the House of the Inhabitant Who Refused is only one of many primitive difference engines. The seventh cell is the unit of difference that energizes the circuitry for a machine of subjective construction and self-generation. Hejduk's obsession with numbers in Vladivostok is initiated, where the One Who Refused must first count himself before generating the proliferation of form, numbering, and naming. The oscillation between the One Who Refused and the absence of a physical subject or zero condition is the territory where the subject falls.2 One does not equal one nor can it be reduced to zero by its apparent absence; instead, the principle of its inequality contains the Lacanian remainder, the object a, which marks the potential space for a network of exchange. Hejduk's replay of the primal scene is thus no longer primary or original but multiplicitous and without origin. Like the seventh cell, each component / masque can be read as a measure of intensity or a nodal point that is able to combine with other masques to form battery-like assemblages within the circuitry of Vladivostok.

Like Kafka's recruiting station / racetrack, the circle of exchange in Hejduk's campo doubles as a racetrack that wagers on the place of the traditional notion of the subject, and as a casting house for the production of the identity of the subject. The Nature Theater's chorus line of imitation angels is not made up of classical caryatid figures of support, but is instead made of structural props marking a threshold at a place that is by definition placeless. Similarly, in gambling parlance, the House of the Inhabitant Who Refused to Participate is a prop house, which is inhabited by players in a shell game where the empty shell / cell, and the crooked prop, is filled in with the number one. Although Hejduk is no gambler, he loads the dice. The House of the Inhabitant Who Refused to Participate is full of holes that leak meaning and develop circuitous routes. As such, it is a fitting ground-zero as well as a delaying station in the construction process of the other mythical architectural beasts that are the citizen / subjects in Vladivostok.

Hejduk's Inhabitant Who Refused is more like Sigmund Freud's subject who doubts than the rational humanist subject who finds order in the world. Just as Freud located the proper place of the subject within the dream, Hejduk defines the citizen / subject as a nomadic character without the property of name or place. The hallucinatory product of exchange between virtual and real in Hejduk's Nature Theater is an improper architecture — a place of improper naming. Actors arbitrarily assume the masque / roles while the parallel numbering system assembles subsystems and affiliations more than it orders.

While the law parcels space into distinct properties, the angelic network cannot be legislated. Hejduk leaves the actual construction of the masques to chance — opening the possibility that they might appear anywhere at any time. There is thus no sense of property attached to grounding the masques. Like the silent dice games practiced in Kafka's mummer's pageant that the masques formally resemble, the rules of the architectural construction are played out as an indecipherable ritual of the converted characteristic of prejuridical models of social organization. The Nature Theater stages an arbitrary justice supported by rules that cannot hold up to scrutiny.

While Kafka's Karl traces a western vectoral movement from Europe to New York and finally toward a fictive Oklahoma on a journey in which he loses his proper identity, Vladivostok reverses direction, geographically and temporally moving toward a premodern society, only to emerge as the other side of the Nature Theater. Kafka's architectural version of Hejduk's seventh cell — the only image offered of the Nature Theater of Oklahoma — is a photograph of the presidential theater box. Like the image of the Inhabitant Who Refused to Participate on the tower, the box is inherently political.

-

Rays of light fell into the box from all sides and from the roof; the foreground was literally bathed in light, white hot soft, while the recess of the background, behind red damask curtains falling in changing folds from roof to floor and looped with cords, appeared like a doskily-glowing empty cavern. One could scarcely imagine human figures in the box, so royal did it look. Karl was not quite rapt away from his dinner, hot he laid the photograph beside his plate and sat gazing at it.3

Traditionally the seventh cell, like the presidential box, is filled by a regal figure — the subject who is not a subject but who possesses and distributes the properties of vision. The king, the first named in the social order, held the place outside the signifying order so that the rational world could define and signify itself by the first principle of non-identity. The monarch was the non-rational residue, the self-organizing and circulating system that operated outside the organization of society. He provided the necessary negative link to the primitive and natural theological order defining the limit condition of the rational by identifying its outer limits. This central figure offers one way of organizing the polis, though it was later superseded by the grid as quantifier and organizer of conformity and exchange in the modern city. Both are models that sanction the stable condition of the ground. The singular nature of the king, however, points toward newer models for a network system without the reoccurrence of a centralizing figure.

Because of the obsessive nature of the objects and their respective characterizations, coupled with the omnipresent hand of the master, Vladivostok appears to contradict the claim that it is a network. Its architecture appears to rescue a mythology of the individual or, at the least, act as a memorial to its tragic disappearance. While there is no seat of power for a president or king, the House of the Suicide, for example, does resemble a head with a crown. But the subject is marked more by its disappearance and the resulting voids, than by the whiteness of the page between each object and its dictionary entry, or by the unresolvable synapses like the seventh cell. Vladivostok's numbers add up to a series of traps where the objects operate as decoys and the names and definitions accentuate the absurdity of searching for meaning. The masques threaten the potential occupant obsessed with maintaining a role. The reductive architectural space of the individual unit is both pathetic and perfunctory. Sustained occupation of any of the masque / cells is suicidal.

Fools rush in where angels fear to tread, yet angels remain as traces in Vladivostok. Before the deliverance of the word in the scene of annunciation, the angel is positioned at the threshold. Neither predictable nor accidental and arbitrary, the angel occupies the space created at the moment of the event. Because it bears no relationship to reality, there is nothing theoretical about Hejduk's urbanism. Hejduk's theory thus marks the possible event itself, the programming of the Nature Theater, and the scripting of the characters who play out roles that only begin to emerge with definitive form. The formal message of the angels always comes too late. Their meaning is contradictory and their unlikely presence and hesitant entry is all that is required to effect space. Within the network of the Nature Theater there is a built-in system of delay and relay that prevents the formation of its architecture, leaving it provisional and unbounded.

In Kafka's Amerika, the immigrant Karl, the everyman precedent of K. in his other novels, experiences homelessness as a state of ecstasy. After continuously trying to define himself in the new world, Karl finally feels at home when he joins the Nature Theater, though he never arrives at his destination. At the unfinished conclusion of the novel Karl is mobile, sitting on a train, headed for an unreachable destination with the possibility that he will reexperience his journey through the novel as another circuitous route. Karl has become angelic, caught at the threshold of becoming with neither name nor proper place. The strategy of the Nature Theater differs from the propriety of the classical theater's reliance on the frame that architecture has used as a model for urban statements and monuments. Like the message of the angel, architecture finds that it has arrived too late and can only define a postmortem on the event. Mimicking the stammering of the angels while staging a ground for the impossible and the improbable, the Nature Theater uses its status as an ill-formed prop to test our faith in the absurd.

Angels hold the place of the many voids left over in Vladivostok. They are found inside the empty spaces of the inversely pitched roofline of the houses that approximate the silhouette of the Angel's wings, and in the holes of the oil paintings where the Director of Medical Services, an expert in angeology, has cut out the winged heads. Hejduk's reference to angels, however, should not be misconstrued as a sign of redemption or as a utopian project depicting an afterlife for the traditional subject. The space of angels does not lie on the other side of the mirror or in a virtual space opposed to the real. Rather, it is a direct projection into the real where subjectivity operates as a monstrous interjection emergent within the overall system. As it circles back upon itself to become yet another superstructure, the utopian aspects of the network should be interrogated as a meaningful urban model. We should not ask what would it mean to be improperly angelic. Rather, we should act as improper angels and demons.

1 gilles deleuze - félix guattari, A Thousand Plateaus : Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Brian Massumi, trans. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 369.

2 See jacques lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, Jacques-Alain Miller, ed., Alan Sheridan, trans. (New York : Norton, 1978), 77.

3 franz kafka, Amerika (New York : Shocken Books, 1946), 293 - 294.

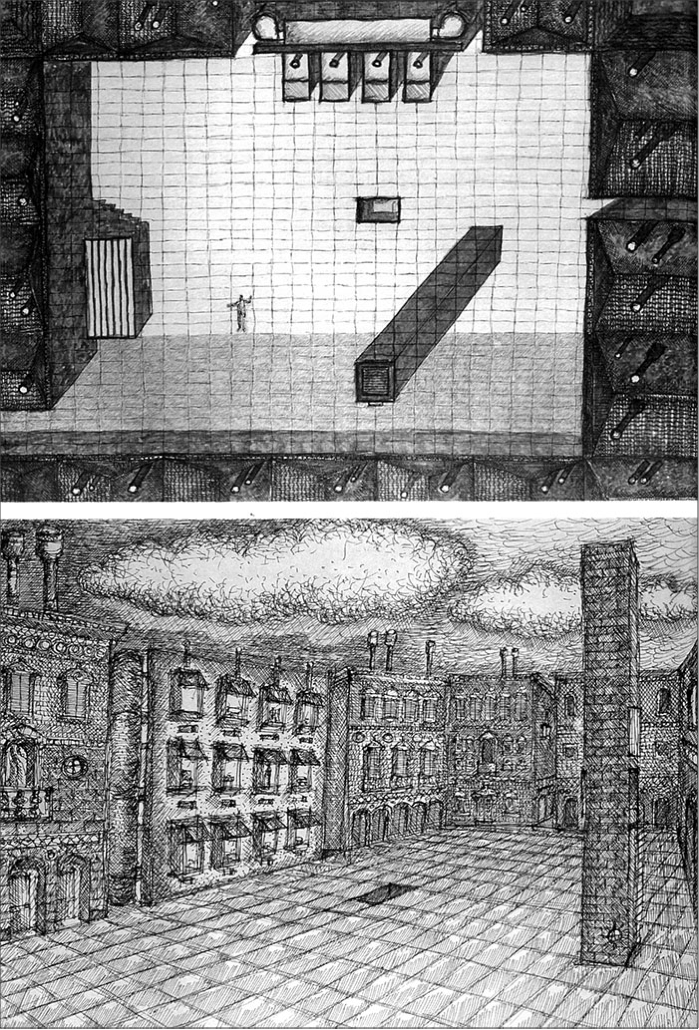

"The Thirteen Watchtowers of Cannaregio," 1978.

Ink on paper, S 1/2 x 11 in. Collection of the Architect.

Courtesy John Hejduk, Architect.